September 9th continued

Tall and lanky, with a proud nose and doe eyes, his demeanor is one of gentle strength and sensitivity. Once we arrive outside the station I am immediately overwhelmed by the multitude of soldiers strolling in groups along the plaza. So young! In their twenties, mostly. I quickly reach for my phone and stop to capture the waves of soldiers criss-crossing the plaza. I tell Nestor that I am stopping to shoot a video. He calmly explains “If you do, you will be arrested.” Oh, of course! Data captured could be used against them by Russian operatives. I am now standing in a war zone, my first.

As we load my backpack into Nestor’s small, modest car, I notice from the corner of my eye a lone soldier, sitting apart from the others. I feel a persistent pull to share with him my arrival and plan, to thank him for his service, and to tell him I understand that he is protecting democracy itself. I mention this to Nestor, and together we walk toward the soldier. Nestor agrees to translate if necessary. We arrive, and sentence by sentence, I watch as my words land within him.

“I‘m from America.

“I’m an artist, and I’m here to paint your soldiers.

“I’ve traveled all the way from California to look you in the eye to thank you.

“I understand you are protecting democracy itself.”

I witness a kind of disbelief, then a gradual reckoning as he understands that I have come all the way from the West Coast of America to his war-torn country, precisely to meet soldiers like him.

I struggle now to describe his expression, a tumult of emotions: gratitude, recognition, the feeling of being seen, honored. Love. Relief. The offloading of trauma. His unforgettable expression I will carry with me through all my days.

As I reach to take his hand, our eyes lock in a sudden intimacy. I bend down to offer a hug as he stands to do the same. We hold one another for a long time, his body trembling so hard, even Nestor notices. I hold and hold him, checking internally that I feel grounded, centered and calm, so that his nervous system can co-regulate with mine. Then we step back, eyes moist. Finally, walking back to he car, I give him a heart sign with my hands, smiling, then a V sign for victory. He smiles back. It is powerful medicine, such an exchange of gratitude.

I was told there is an easel in the guest room – a welcome bonus to my homestay. I arrive to discover the entire attic of the home has been converted into a fully equipped art studio. Countless easels, work tables, and a sewing machine arranged on the paint-splattered floor, all illuminated by skylights. Canvases and brushes and tubes of paint are scattered everywhere. A tribe of artists, birthed into the same cradle, my brethren of mind and spirit, a natural ease and understanding between us.

Nestor and I arrive at the local art supply store, and I’m grateful I schlepped my sizable watercolor bloc all the way from California. His sister and housemate, nineteen-year-old Yuliana, had assured me that these stores in Lviv were fully stocked. The shop only offered one very small bloc. I purchase it in any case, along with a sketchbook and other supplies, including watercolor paints made in Ukraine. I contemplate painting just the eyes of the soldiers in the small bloc. Instead I intentionally leave it behind in my host family’s art studio; a kind of promise to return, an excuse and willful obligation.

In the evening I receive a text from Luka’s mother with the contact info of a famous wounded soldier in Lviv, Volodymyr (Vlodo), saying he was briefed on my project and is waiting to hear from me. I message him and include examples of my portrait paintings.

Sept 10

By this morning I have not heard back from Vlodo the soldier. So I phone him in what turns out to be a cold call. His English is good and he is very open to participating in my project. He’s also an artist, and is coming to the house tomorrow afternoon to sit for me.

After breakfast, Nestor gives me a brief tour of the neighborhood, including a site where missiles struck a few blocks away, a week and a half before my arrival. Seeing the scale of destruction in person is sobering. Another of the missiles was intercepted nearby, and broke the windows in our house simply from its shock waves.

Before Vlodo arrives tomorrow, I have an interview with Andriy, Director of External Communications and Olga Rudneva, CEO at Superhumans, the organization providing rehabilitation of wounded soldiers fitted for prosthetics, as well as psychological support. They are concerned about how I may react emotionally to seeing all the injuries when I see them en masse. Just as I painted in the past, a scorpion clinging to a wall in my Italian house-church in order to come to terms with the fact I was now cohabitating with scorpions, I’ll process what I encounter through the act of painting it.

I anticipate telling the soldiers my story of seeing a beautiful boy years ago with multiple scarring on his face. These scars amplified his beauty, especially to those who appreciate that, individuals with depth and sensitivity. There exists the grand possibility of reframing injuries as newfound beauty, as the young Ukrainian photographer Marta Syrko has done in her Soldier Series – creating images of amputee soldiers that conjure up Greco-Roman sculptures, whose beauty is still profoundly celebrated, in spite of the missing limbs.

While I was initially cautious that I might not be accepted here in Ukraine, that my trust in my self-worth might somehow turn out to be a perverse reverse-imposter syndrome, my worth has been consistently validated, amplified even, by everyone here: friends of my new acquaintances, the soldiers, a shopkeeper. I ask Nestor to explain to the young girl at the art supply store why I am here. He translates for me. Her reply is “You are breaking my heart.” We hug.

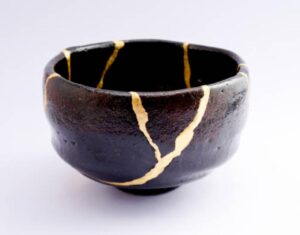

Kintsugi in Ukraine

A broken bone is often stronger at the break after it heals. This concept can be applied to trauma held in the body, mind, and nervous system: the injury contains within itself the possibility of a new strength. The injury must be transformed, healed, allowing wisdom to replace the psychological wounding.

My goal in Ukraine is to transmit a kind of kintsugi; bring beauty and strength where there is a wound.

My partner back home was correct; Eastern Europe is like a second-world country. He was not so concerned that a missile might land on me, but rather my cab driver would hit a pothole, damaging my neck irreparably. As I transferred from train to bus to circumvent the broken tracks in Poland’s railway, I tripped and fell at the very bottom of the cement staircase, landing (fortunately) on my knees in gravel, my leather travel pants providing protection. No broken skin, just bruising. No ice on the bus nor the subsequent train, so I applied constant pressure with my hands to reduce inflammation. It worked. Thankfully, my knee is fine. Outside the art supply store Nestor and I visit, the little plaza has a pothole that could easily swallow a Smart Car, but the city obviously has other more urgent priorities than repairing such a hole.

September 11

It’s the twenty-second anniversary of the day my father phoned to say “Sasha, we’re at war.” Only now do I understand what being at war is like.

Today I will arrive at Superhumans. I’m nervous and turn to parasympathetic breathing exercises. I’m dressed causally, in black leggings, flip flops, a fitted ochre tank top, and a blue and yellow silk scarf with Van Gogh’s sunflowers strewn across it; Ukraine’s national flower.

My taxi passes through Lviv’s urban center, which gives way to suburbia, and finally countryside as we approach Superhumans. Along the way we pass a cemetery brimming with massive floral arrangements and blue and yellow flags decorating countless fresh graves. We arrive at our destination, are checked in at guardhouse and pull up to an external office where I am greeted by Andriy, my public relations contact at Superhuman’s newly remodeled state-of-the-art facility. His energetic playfulness and warm smile are disarming, which helps me with my encounter with Olga, Superhuman’s CEO. Wearing black leather and rubber, she is all business and not a little intimidating. I hastily explain “I’m a sensitive artist. I might cry for ten seconds when I meet the soldiers and then I’ll be fine.” She shook her finger near my face and said “You won’t cry!” and my hand instinctively snapped to my forehead in a military salute. “No!” she countered, “You don’t understand. It is so positive in there, you won’t cry.” I suddenly felt as if I were starring in a surrealist film, dumbfounded by her prediction.

But true to her word, as I walk past the freshly painted walls to the dreamy, modern reception area, upbeat music playing with a watery video projected on the wall behind the front desk, I feel I’ve stepped into another world. I’m surrounded by a dozen amputees, joking among themselves while sitting and standing around a beverage station. Andriy gives me a tour of the facility: a gym with specialized equipment, a therapy pool that rivals anything a world class resort could offer (complete with inflatable rainbow unicorn float at one end), and a carpeted recreation room on the top floor with a foosball table and basket swings hanging from the ceiling. With low lighting and a handful of windows overlooking the construction area where the facility is expanding, this room will be the perfect spot to paint my soldiers.

I use the word “soldiers” here loosely, as nearly all whom I paint are volunteers with no previous military training. I will eventually paint: a scholar, a train operator, a truck driver, a musician, a puppeteer, a carpenter, all of whom left their professions and families behind to risk their lives defending their towns, their neighbors, their way of life.

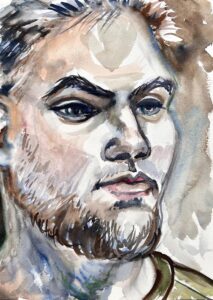

After not painting portraits for what feels like a lifetime, I still have my chops. Strolling past the Barbie doll on display fitted with a prosthetic leg on my way back to the reception area, a man of slight build and height named Dmitry (Dima) approaches me. He walks right up, briefly introducing himself, and asking directly “What is your name?” “Where are you from?” then “Why are you here?” I answer, then ask “Would you like me to paint you?” – “Yes!” he replies. He later flirts with me that he is “my first,” and will always be “my first”. His former, pre-military life was producing children’s events and parties, dressing up in costumes (another artist!). We do not speak of his experiences in the war (he lost a lower leg), but rather we swim in a stream of relentless positivity that Superhumans generates. It’s their driving philosophy; there is zero tolerance for anything less.

While painting Dima’s tranquil face, something deeper comes through my subconscious that infuses his warrior experience into the portrait. He glimpses the image in process, exclaiming “Oh! Fierce!” and we marvel at how his deep experience is being communicated somehow between our bodies.

Later that afternoon, I return via taxi to my homestay studio to paint Vlodo, the gentleman whom I’d been connected with through Luka’s mother. A fellow artist-turned-volunteer soldier, his gentle demeanor and quiet strength put me immediately at ease. During my painting process I feel comfortable asking him, with his permission, what it was like being stationed at the frontline. Noticing the scar on his shoulder, he briefly explains his injury; shrapnel has lodged in his shoulder girdle, inoperable. If his body is unable to encase the object with cartilage, his range of motion will remain debilitated. If it does manage to cover the object and heal, he will go right back to the front.

He explains his belief that spirituality and science can co-exist. Before COVID lockdown, he was enrolled at a university writing poetry utilizing microbes growing in a petri dish. I was fascinated, and encourage him to continue his project that had been interrupted by COVID. He cautions me that he can only realistically plan ahead one week at a time.

We talk about coming to terms with death, about the complete elation he experienced while liberating a village in the Donbas in the autumn of 2022, reclaiming occupied territories. “Elderly women, tears of gratitude streaming down their faces, approached our tanks, bouquets of wildflower offerings in their hands. Then, later in the evening, being in a trench and watching your brother-in-arms being blown up in front of you…” his voice trails off. “Losing a fellow soldier like that feels like losing your grandmother.” He adds that if he indulged in recollections of home or loved ones while at the front, the emotional pain was so great he had to stop himself, and practice mindfulness instead.

At midnight, I am pulled to call my best friend and chosen mother back home, Mama Burt, and wish her a happy birthday. Of anyone, she would understand my experiences with the soldiers here, she who lived through and survived the Iranian revolution. She who was held at gunpoint at a fake checkpoint in Africa, until the thieves understood their captives were professional teachers, and rather than murdering them, begged them to come to their village to teach their children. I need to tell her that today was one of the most extraordinary of my life.