September 12th (continued)

The sprawling hospital facility is not as polished as that of Superhumans, but it’s just as buzzing with activity. I receive a tour that ends in the workroom of their resident art therapist. The tall, soft-spoken social worker explains his goal in art therapy is to minimize trauma. His clients’ artwork spread out on a table before us, he chooses the pastel paintings of a volunteer defender, showing me a series in chronological order: on a black background an ovoid, child-like face engulfed in red flames, then a group of faces engulfed in flames, then an outline of the artist’s hand on black with colored flakes added, and finally, a peaceful landscape of a cool blue pool, green trees, and blue sky. Mykailo, the artist, watched several of his brothers-in-arms burned alive in a tank, and is struggling to process the trauma. He himself lost a leg at the frontline.

Finally, we arrive in the facility’s gymnasium, where a dozen or so men missing various body parts are lined up on mats doing floor exercises, under the instruction of a petite but fierce blond instructor. Julia announces why I am there. The farthest from me volunteers his mat-mate, gesturing “Paint him! But you have to paint him naked.” Laughter erupts. I counter “Well, he won’t be my first, and he certainly won’t be my last” and now they are rolling with laughter. I’m accepted into their community.

The nearest man looks up at me with the palest of blue eyes, set in a long and chiseled face, a thin and curly Mandarin beard decorating his tan complexion. His tall, lean frame is missing a leg at the hip. I secretly wish to paint him, but say nothing.

This morning I realized there most certainly is an entire community of survivors with catastrophic brain and head injuries, existing in the shadows; those unlucky to have survived, severely diminished. They are hidden away so as not to despair visitors. But certainly they are existing in the back rooms of some institutions and homes… my queries are confirmed by several individuals.

Next stop is George’s room, the man who was volunteered to be painted naked. I play along and tell him to remove all his clothes. He reluctantly begins to do so, when I stop him and confess I was just teasing. As I paint his young face, he shares he was injured in Bakhmut, suffered a series of strokes and lost his dominant forearm, coming to terms he may never play his guitar again. Tired of institutional food, he orders sushi for us, and I employ the empty cells of my palette as dipping trays for soy sauce, wasabi and pickled ginger.

He shares the room with three other patients, and one volunteers to be painted next. Constantine was a train operator before the full-scale invasion, and after military training, found himself in charge of a hundred men. He explains in a gentle voice that during battle, he stepped on a land mine, lost his leg and is recovering also from shrapnel injuries. I notice his body is riddled with scars as he sits posing for me in his hospital bed, a Ukrainian flag tacked to the wall behind him.

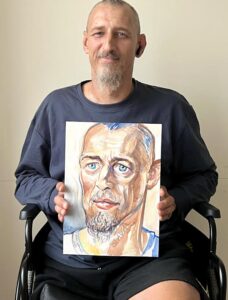

After an afternoon break for pizza at a nearby restaurant, we return to Unbroken where I will paint the soldier whose artwork I saw earlier. Mykailo appears calm and jocular as he poses for me in the small, stark community room on his floor, but his demeanor masks his internal world. When I comment on how serene he appears, he immediately questions “Do I? Are you sure? I look okay?,” and I see how he is still struggling to recover from his traumatizing battle experiences. Like Dima before him, something is coming through my subconscious infusing my painting; in this case, a fear bordering on terror. I stop, and explain what is happening without revealing specifics, asking Mykailo “Do you want me to paint what is coming through, because you will be taking this home with you to your family.” He requests that I paint what is coming through, but in the end, I haven’t the heart, so I shift to what I imagine his healed, future-self will look like: relaxed with a regulated nervous system. It can serve as a beacon on his path to recovery.

That evening I receive a text message from Julia inquiring about the television interview at Unbroken. I’m confused, as my scheduled interview is at Superhumans. The text turns out to be from a new journalist (coincidentally named Julia) covering for Lviv’s Pershyi Zahidnyi. I welcome yet another interview on September 14th, with her at Unbroken.

Vlodo texts, inviting me out now with his girlfriend to explore Lviv’s nightlife, and I accept. We share a traditional Ukrainian meal, then wander about the city, exploring art galleries and bars. One painting exhibition features animals and humans resisting trees that caught fire from missiles, and floating in floodwaters from the sabotaged Kakhovka dam on the Dnipro River. The ensuing flood demolished towns, killing people and animals, damaging farmland and infrastructure; an epic, manmade environmental disaster.

Sept 13

Back at Superhumans, one of my soldiers, Oleg, is a theology scholar who studied in Rome. When a soldier is escorted in to be painted, my first question is “Do you speak English?” In this case the answer is no, so I say in passing “Oh well, I only speak English and Italian.”.– “Parli l’italiano?!!” My chatty sitter and I converse in Italian throughout the painting process. Oleg’s entire left side is compromised: he lost both his left arm and leg, left kidney, and sustained major blood loss on the battlefield. His entire left side is filled with shrapnel. He can stand comfortably on one leg, bend his knee until he reaches the floor, and stand up again all on his own. When people approach him while he’s sitting, he immediately stands to shake their hand. “Oh, you’re tall!” they say, rather than fixating on his missing limbs. A colleague visited him while he was recovering in the hospital to encourage him to finish writing the book he was working on before being injured. He replied “Yes, and write my next book as well!”. Oleg is the epitome of resilience. He says “We’re taught here never to say ‘Goodbye’, but rather ‘See you later’ .” He shares a host of neuroplasticity techniques that he’s learned, including placing past, challenging experiences ‘over your left shoulder’, physically gesturing this as he speaks.

Next I paint Henadiy, a double-leg amputee, with head and facial injuries, one eye almost shut. He sits quietly, his sheer presence so intense we hardly speak, even though his English is perfect. He is one of my favorite subjects, with his shaved head one can see all the sculptural details of his distinct features. At one point I tease him that his left, open eye is the intelligent one and the other, half-closed, the sexy one. I explain the art of kintsugi and he understands he is living proof of it. He’s clearly transmuted his trauma. Toward the end of our sitting, I ask him “How are you doing (really)?” He replies “I’m good. This is my reality” pointing to his prosthetic limbs “and I accept my reality. I cannot wait until I am proficient on these so that I can return to the front. It is all I think about, our undisputed victory over the invaders.”

My last painting of the day is of a man with such exotic beauty it is hard to meet his eyes. Sergiy has crazy cheekbones and the palest of blue eyes with dark outlines delineating his irises. Lavender lips and olive skin. A tall, lanky frame with a strong and wiry upper body. Right leg in a complete soft cast with foot twisted, dangling limply, but with his ability to move his toes. I ask with some hesitation if he killed many Russians, gesturing with my hands (he speaks no English) tat tat tat and “Russia?” He explains he operated a rocket launcher and killed many, a look of seriousness and pride. Before he leave, I asked motioning with my fingers if he will be able to walk again. He nods “Yes” with a confident smile.

I take a break and wander the halls, soldiers are flirting with me in the hallway…

Andriy, my liaison, who until yesterday evening was often a sarcastic joker, finally lets his guard down while walking me to my taxi home. He confesses that many people visit and have almost no reaction – “They come and have a look around, then leave. But you bring so much light!”

September 14th

I’m in the waiting area at Unbroken, looking forward to my next painting session, and second television interview. The television crew arrives and we decide to start the interview in the well-lit glassed-in walkway connecting two of Unbroken’s buildings. Yuliana, my lovely housemate has decided to join me on today’s visit, and she winds up translating the crew’s questions for me. The interview goes very smoothly, then moves to the communal sitting area-cum-studio to document my next portrait session.

My soldier enters the space and I blush – it’s Slava, the handsome man from the gymnasium the other day who was situated nearest to me. I am thrilled to paint his fine bone structure, olive skin, twinkling blue eyes and full lips. He led an active life as a carpenter before the full-scale invasion. Now, he navigates on crutches as his left leg is amputated at the hip joint. While he appears calm and relaxed, both terror and bravery are transmitted through the paintbrush and this time I allow it. We’re both extremely satisfied with the portrait.

On my way out, a young soldier named Ivan asks to be painted. My portraits are generally taking about an hour an a half to complete, but we only have half an hour so I create more of gesture study. While painting him, a strawberry blonde man in a wheelchair, entire right side paralyzed, comes toward us locomoting with his left leg. His speech is slurred but it’s obvious he, too, wants his portrait painted. He understands English, and I assure him I will return to paint him in a couple of days. He comes close and rests his head on my stomach and I cradle it. He is so authentic and loving, I hope to do justice to his portrait.

Back at home, my housemate Yuliana expresses how challenging it is to communicate with her soldier friends who are returned from the war. She describes herself as a people-pleaser, and feels awkward as she doesn’t know what to say to them in order to be helpful. I suggest she simply focus on being present in her body and ground herself. In this way she can help ground her friends and bear witness to whatever it is they have to share with her.